Sometime today the Rev. Richard Ingalls will have arrived at Mariner's Church, the Detroit congregation that he has faithfully served since 1965. And within the stone walls of the edifice, Rev. Ingalls will have tolled the church bells, letting the sound echo across the city. It is a ritual that Ingalls has done each November 10th for the past thirty years, ever since that first dawn in 1975 when Ingalls' moment of grief was forevermore put into the annals of American folklore...

In a musty old hall in Detroit they prayed

At the Maritime Sailors' Cathedral

The church bell chimed 'til it rang twenty-nine times

For each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

It was thirty years ago tonight that the

S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald - one of the largest and by far the most well-known of the bulk iron-ore freighters plying the Great Lakes, sank in a fierce November gale, taking with it the lives of all 29 crewmen aboard. It has since become one of the most famous shipwrecks in American history.

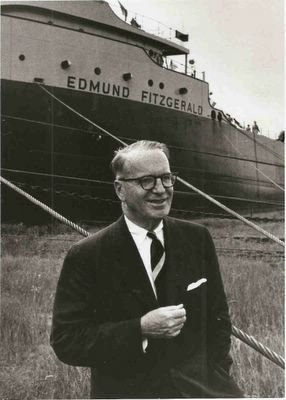

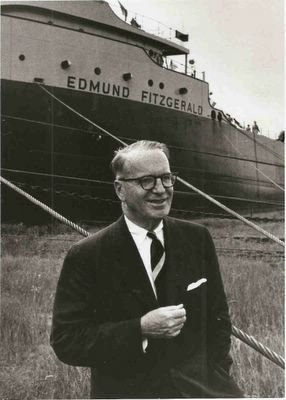

In 1957 the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin signed a contract with Great Lakes Engineering to build what was meant to be the first "maximum sized" Laker in existence. Hull 301's keel was laid that August, and a little over a year later the vessel was launched and delivered to her new owners. The ship was named after Edmund Fitzgerald, one of the CEOs of Northwestern Mutual, with his wife having the honors of christening the massive craft.

In 1957 the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin signed a contract with Great Lakes Engineering to build what was meant to be the first "maximum sized" Laker in existence. Hull 301's keel was laid that August, and a little over a year later the vessel was launched and delivered to her new owners. The ship was named after Edmund Fitzgerald, one of the CEOs of Northwestern Mutual, with his wife having the honors of christening the massive craft.

"The Pride of the American Flag", she was called, as well as "the Queen of the Great Lakes". At 729 feet long and 75 feet wide, the Edmund Fitzgerald held the title of largest ship on the lakes throughout most of her life. She had the capacity to carry more than 26,000 tons of iron pellets from mining operations on the western end of Lake Superior to the steel mills of Detroit, Toledo, and other ports in the east. Early in her career she broke cargo records, including that of carrying over a million tons of ore through the Soo Locks that separate upper Michigan from Ontario.

But as much as she owed it to her girth, the Edmund Fitzgerald became a fixture in the lives of those who lived along the lakes because of the antics of her crew also, especially those of longtime captain Peter Pulcer, who was ever eager to entertain those on shore. Good luck came when she steamed past some town or village on the shoreline: children, college students, steel-mill workers and homemakers ran onto beaches from Superior to Erie to wave at the ship. It was a part of life.

As the years progressed, the Fitzgerald garnered a storied history. Its crew was widely known to be a colorful, jovial lot, full of life and love for the lakefolk, and to serve on her was deemed a great honor around the Great Lakes. She was, by every account, the most beloved vessel sailing on the Great Lakes, and widely considered to be one of the most elegant ever put to water.

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

when the skies of November turn gloomy.

On November 9th, 1975, the

Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin, on the westernmost side of Lake Superior. In her hold was over 26 thousand tons of iron ore, bound for Detroit and the steel mills, in was to have been a straightforward route across the lake and into Huron. She had a crew of 29 and at her helm was Ernest McSorley, every bit the "good captain well-seasoned", with 44 years of piloting the lakes under his belt in a respected career.

And later that night when the ship's bell rang,

could it be the north wind they'd been feelin'?

There are few things, it is said, that are more fierce than a Great Lakes storm in November, such as the one of November 10th, 1975. A massive low-pressure cold front churned across the plains and headed north toward the lakes. On the 9th the Coast Guard issued a gale-force warning to all ships on Superior. Captain McSorley radioed the Coast Guard and the captain of another ship, the

Arthur M. Anderson. Both the

Fitzgerald and the

Anderson headed further north, closer to Canada and away from the terrific waves that would be produced in open water.

The wind in the wires made a tattle-tale sound

and a wave broke over the railing.

And ev'ry man knew, as the captain did too

'twas the witch of November come stealin'.The dawn came late and the breakfast had to wait

when the Gales of November came slashin'.

When afternoon came it was freezin' rain

in the face of a hurricane west wind.

Early on the 10th the front arrived over Superior. The ship weathered a battering morning, but both the

Fitzgerald and the

Anderson were considered safe: the winds had thus far come from the northeast, affording the ships the buffering of nearby land.

But that changed as afternoon progressed, when the winds shifted to the northwest, robbing the ships of their protection. The Anderson later reported that the winds reached 43 knots, with 16 foot waves crashing against the hulls. When the Fitzgerald radioed in, it was listing to one side, had suffered vent damage and the loss of a rail. Later the ship lost both radar arrays, had listed even more, and the waves were getting higher, crashing onto the deck. Despite the damage, the Fitzgerald pressed on.

Later that evening the Anderson picked up the Fitzgerald on her radar. Radio contact was established. And at 7:10 pm came the final message ever heard from the Edmund Fitzgerald:

"We are holding our own."

Shortly thereafter the

Edmund Fitzgerald disappeared from radar, never to be seen above the surface again. All 29 crewmembers rode her down to the bottom of Superior.

The captain wired in he had water comin' in

and the good ship and crew was in peril.

And later that night when 'is lights went outta sight

came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

No one is certain what happened to make the

Fitzgerald sank, but many experts believe that faulty cargo hatches, discovered a few days earlier, were a prime culprit. As the

Fitzgerald continued in the storm, water from the rain and waves was saturating the iron ore: the ship becoming heavier the longer it was at sea. It is believed a wave overcame the overly-stressed vessel, sending it sinking without warning or a chance to recover. Expeditions to the

Fitzgerald later found that the ship had snapped in two.

Route of the Edmund Fitzgerald's final voyageThe following day's newspapers screamed the loss of the "Fitz". Thousands came to Superior's shores to weep and pray for the lost. And on Jefferson Avenue in Detroit the Rev. Richard Ingalls peeled the church bell twenty-nine times - one for each man on the Fitzgerald - from the Old Mariners Church. He has done so each November 10th since, ringing the bell thirty times: one for each crewman and once more in memory of all those who have lost their lives in the Great Lakes.

All that was left of the Fitzgerald were some of the lifeboats found afterward and the ship's bell, later recovered and restored to rest in a museum in Whitefish Point, Michigan. The ship rests in over 500 feet of water 17 miles from Whitefish Bay.

The following year Canadian singer Gordon Lightfoot released a six and a half minute song. It has become one of the most haunting ballads in history: "The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald"...

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they called "Gitche Gumee"

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomyWith a load of iron ore twenty-six thousand tons more

Than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty

That good ship and true was a bone to be chewed

When the "Gales of November" came early

The ship was the pride of the American side

Coming back from some mill in Wisconsin

As the big freighters go, it was bigger then most

With a crew and good captain well seasoned

Concluding some terms with a couple of steel firms

When they left fully loaded for Cleveland

And later that night when the ship's bell rang

Could it be the north wind they been feelin'?

The wind in the wires made a tattle-tale sound

And a wave broke over the railing

And ev'ry man knew, as the captain did too

'twas the witch of November come stealin'

The dawn came late and the breakfast had to wait

When the Gales of November came slashin'

When afternoon came it was freezin' rain

in the face of a hurricane west wind

When suppertime came the old cook came on deck sayin'

"Fellas, it's been too rough to feed ya"

At seven P.M. a main hatchway caved in, he said,

"Fellas, it's been good t'know ya"

The captain wired in he had water comin' in

And the good ship and crew was in peril

And later that night when 'is lights went outta sight

Came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Does anyone know where the love of God goes

When the waves turn the minutes to hours?

The searchers all say they'd have made Whitefish Bay

If they put fifteen more miles behind 'er

They might have split up or they might have capsized

They may have broke deep and took water

And all that remains is the faces and the names

Of the wives and the sons and the daughters

Lake Huron rolls, Superior sings

In the rooms for her ice-water mansion

Old Michigan steams like a young man's dreams

The islands and bays are for sportsmen

And farther below Lake Ontario

Takes in what Lake Erie can send her

And the iron boats go as the mariners all know

With the Gales of November remembered

In a musty old hall in Detroit they prayed

at the Maritime Sailors' Cathedral

The church bell chimed 'til it rang twenty-nine times

For each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they call "Gitche Gumee"

"Superior" they said, "never gives up her dead

When the gales of November come early!"

Thirty years ago... it only seems like a long time. I was a year and a half old when the

Fitzgerald foundered. A very young man still, but we look far across and above how we were thirty years ago. Above losing a mighty ship to the elements, certainly. And then we remember that the

Fitzgerald is still a living memory in the hearts of the wives, sons, and daughters of her crew. We stand reminded that we are not masters, but come into each new day by the grace of God. And it's only by the grace of God that we can end the day warm in our homes.

Shipwrecks have gained new romanticism in the past few years with the interest in the Titanic. There have been times when the Fitzgerald has been compared to the doomed ocean liner, but that's wrong. The Fitzgerald wasn't a symbol of extravagance and opulence. She wasn't some far-removed spectacle beyond the dreams of the children who saw her. The "Fitz" was a component of their lives, something to take pride in. The Fitzgerald wasn't an exercise in vanity, but a good ship with a good crew, doing the best job it could.

Which would have been something to boast of more in the years to follow: to have ridden in comfort above the Titanic had she survived her maiden voyage, or to have worked hard alongside such men as on the Fitzgerald? I don't know about you, but my life would have been far richer to have been aboard the "Fitz", if only just once.

Anyway, since it will be thirty years ago tonight that the Edmund Fitzgerald was lost, I thought that a tribute was appropriate, in the best way that I know how. Gordon Lightfoot's ballad is the very first song that I can remember hearing, so this story has some kind of special meaning to me. This could be considered the last great shipwreck in American history: there has to be a sobering respect for that.

Here's to a good ship and crew...

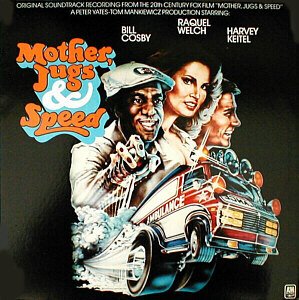

(Some of this was adapted from a piece I wrote five years ago, but didn't have the opportunity to publish like I had wished. It's presented again here, on my own forum.) I was just checking the TV listings for this evening and if you've got the Fox Movie Channel and haven't "gotten" into Lost yet, you got a real treat tonight. At 8 p.m. EST they're running Mother, Jugs & Speed, starring Bill Cosby, Harvey Keitel, and Raquel Welch. It's a nice little gem from 1976 about a private ambulance company that's fighting both a competitor for a contract from the city, and its own internal conflicts. Bill Cosby is "Mother": the hardened veteran driver who flaunts all the rules in the book (and has a penchant for scaring nuns while driving his rig). Harvey Keitel is "Speed", and that handle doesn't necessarily reflect how fast he drives either (he's a suspended cop suspected of drug dealing). Raquel Welch is "Jugs": the outfit's dispatcher who wants to work the ambulances like the big boys. Look for more familiar faces like Larry Hagman and Dick Butkus among the cast. It can be a sometimes disturbing movie, especially if you're a fan of Bill Cosby. Be warned: this is the darkest comedy that the Cos has ever done in his career that I can think of. But it's also a pretty darned hilarious movie too: the scene where the lady's stretcher is going out of control down the street cracks me up every time I watch it! Plus, this movie absolutely has one of the all-time funkiest theme songs. Just wait 'til you hear it, you'll have "DANCE!" in your head all night.

I was just checking the TV listings for this evening and if you've got the Fox Movie Channel and haven't "gotten" into Lost yet, you got a real treat tonight. At 8 p.m. EST they're running Mother, Jugs & Speed, starring Bill Cosby, Harvey Keitel, and Raquel Welch. It's a nice little gem from 1976 about a private ambulance company that's fighting both a competitor for a contract from the city, and its own internal conflicts. Bill Cosby is "Mother": the hardened veteran driver who flaunts all the rules in the book (and has a penchant for scaring nuns while driving his rig). Harvey Keitel is "Speed", and that handle doesn't necessarily reflect how fast he drives either (he's a suspended cop suspected of drug dealing). Raquel Welch is "Jugs": the outfit's dispatcher who wants to work the ambulances like the big boys. Look for more familiar faces like Larry Hagman and Dick Butkus among the cast. It can be a sometimes disturbing movie, especially if you're a fan of Bill Cosby. Be warned: this is the darkest comedy that the Cos has ever done in his career that I can think of. But it's also a pretty darned hilarious movie too: the scene where the lady's stretcher is going out of control down the street cracks me up every time I watch it! Plus, this movie absolutely has one of the all-time funkiest theme songs. Just wait 'til you hear it, you'll have "DANCE!" in your head all night.

The Sun over in Great Britain

The Sun over in Great Britain

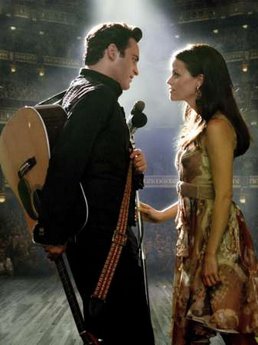

Starring Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon, Walk The Line depicts the first thirty-odd years of Cash's life, from growing up in rural Arkansas up to the beginning of his marriage with June Carter. The film opens in 1968, minutes before Cash (Phoenix) began recording his live concert at Folsom Prison. A table saw in the prison's woodshop triggers a flashback in Cash's mind: 1944 and a young J.R. Cash listening with his brother Jack to the Carter Family on the radio, with Johnny picking out 14-year old June's voice. We are introduced to Johnny's father Ray - played by Robert Patrick, who has come a long way as an actor from an already great role he had as the T-1000 in Terminator 2: Judgement Day - and mother Carrie (Shelby Lynne). It's not long afterward that we witness the event that dwelled on Cash's mind for the rest of his life: brother Jack nearly cut in two by the table saw in the woodmill that he worked in, lingering long enough to tell his family about seeing Heaven.

Starring Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon, Walk The Line depicts the first thirty-odd years of Cash's life, from growing up in rural Arkansas up to the beginning of his marriage with June Carter. The film opens in 1968, minutes before Cash (Phoenix) began recording his live concert at Folsom Prison. A table saw in the prison's woodshop triggers a flashback in Cash's mind: 1944 and a young J.R. Cash listening with his brother Jack to the Carter Family on the radio, with Johnny picking out 14-year old June's voice. We are introduced to Johnny's father Ray - played by Robert Patrick, who has come a long way as an actor from an already great role he had as the T-1000 in Terminator 2: Judgement Day - and mother Carrie (Shelby Lynne). It's not long afterward that we witness the event that dwelled on Cash's mind for the rest of his life: brother Jack nearly cut in two by the table saw in the woodmill that he worked in, lingering long enough to tell his family about seeing Heaven.

This just reeks. I'm literally at a loss for the words I'm looking for to convey how low my heart feels right now. Being a child of the Eighties, Mister Miyagi was one of my heroes. One minute he was this cute little handyman trying to catch houseflies with chopsticks. The next he was this engine of rage karate-chopping hoodlums into pain and agony. "Wax on, wax off!" The guy became, I think it's safe to say he became a genuine archetype of wise master, right up there with Gandalf and Obi-Wan Kenobi.

This just reeks. I'm literally at a loss for the words I'm looking for to convey how low my heart feels right now. Being a child of the Eighties, Mister Miyagi was one of my heroes. One minute he was this cute little handyman trying to catch houseflies with chopsticks. The next he was this engine of rage karate-chopping hoodlums into pain and agony. "Wax on, wax off!" The guy became, I think it's safe to say he became a genuine archetype of wise master, right up there with Gandalf and Obi-Wan Kenobi.

In 1957 the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin signed a contract with Great Lakes Engineering to build what was meant to be the first "maximum sized" Laker in existence. Hull 301's keel was laid that August, and a little over a year later the vessel was launched and delivered to her new owners. The ship was named after Edmund Fitzgerald, one of the CEOs of Northwestern Mutual, with his wife having the honors of christening the massive craft.

In 1957 the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin signed a contract with Great Lakes Engineering to build what was meant to be the first "maximum sized" Laker in existence. Hull 301's keel was laid that August, and a little over a year later the vessel was launched and delivered to her new owners. The ship was named after Edmund Fitzgerald, one of the CEOs of Northwestern Mutual, with his wife having the honors of christening the massive craft.